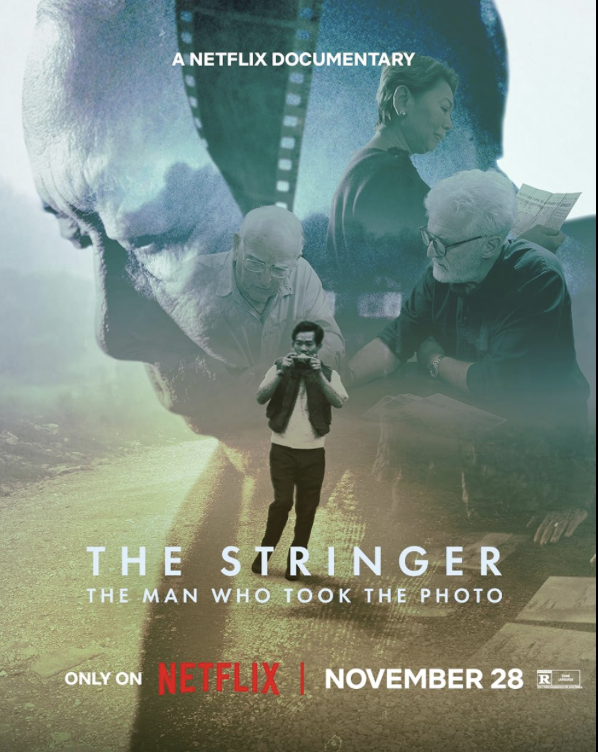

The Stringer Documentary: My Honest Take on the Famous Leica Napalm Girl Photo

The Stringer, “Napalm Girl,” and an Uncomfortable Conversation by Justin Mott

For fifty years, we believed the Pulitzer Prize– and World Press Photo–winning image known as “Napalm Girl” was a Leica photograph made by Nick Ut.

A new documentary challenges that assumption.

It suggests the photograph may instead have been taken by a Vietnamese stringer using a Pentax—someone who lived his entire life without credit for one of the most important images in photojournalism.

I recently watched The Stringer, and I have thoughts. This piece contains spoilers, so consider that fair warning.

I first heard about the film earlier this year as it made its way through the festival circuit. The premise alone—that Nick Ut may not have taken the photograph—immediately caught my attention.

I’ve lived and worked in Vietnam for nearly two decades and have photographed here extensively, including more than one hundred assignments for The New York Times. Stories like this matter deeply to me, not just as a photographer, but as someone who has spent a long time trying to understand this place and its history.

When I learned that Gary Knight was involved in the documentary, my interest grew.

I don’t know Gary intimately, but I know him well enough to say this plainly: I respect him. He’s thoughtful, principled, and deeply committed to photography as both a craft and a responsibility. A conflict photographer, an educator, and a co-founder of VII, Gary has contributed meaningfully to this field. He’s also not someone who takes ethical shortcuts.

That context matters.

At the same time, I want to be clear about my position. I don’t know Nick Ut personally, but people I trust speak well of him. I wasn’t part of that era. I’m not competing with him. He doesn’t live here. And this isn’t about attention, jealousy, or career positioning.

I’ve had more professional success than I ever expected or needed—editorial work, a television show, and a commercial photography and production company in Vietnam. My YouTube channel exists because I enjoy teaching and sharing perspective, not because I want controversy.

In fact, I dislike covering polarizing topics. They genuinely make me anxious. I’d much rather be at home with my wife and our dogs, riding my bike, working on personal projects, or trying to improve my golf game.

But enough people asked for my perspective—privately and publicly—that I felt it was worth engaging with this honestly. And because of the sensitivity of the topic, there are no sponsors attached to this discussion.

What ultimately pushed me to speak was seeing journalists dismiss the documentary outright, saying they didn’t need to watch it to know it was wrong.

That isn’t journalism. It isn’t curiosity. It’s choosing comfort over inquiry.

You don’t get to reject new information simply because it challenges a narrative you’ve grown accustomed to.

The documentary centers on claims made by Carl Robinson, the Associated Press photo editor in Vietnam at the time the image was transmitted. Robinson says Nick Ut did not take the photograph and that his boss, Horst Faas, instructed him to credit Ut instead of the actual photographer.

The image went on to win both the Pulitzer Prize and World Press Photo of the Year. Nick Ut built a decades-long career around that single frame.

The film introduces Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, a Vietnamese stringer who Robinson tracked down years later. Robinson eventually meets Nghệ in a hospital after Nghệ suffered a stroke and apologizes to him.

Nghệ and his family say he took the photograph.

According to Nghệ, Faas paid him for the image and gave him a print. If Nghệ hadn’t taken the photo, there would be no reason for an editor to give him one. His wife later destroyed the print because she didn’t want such a graphic image in their home, but she kept a newspaper clipping of the published photograph. That clipping was discovered during the making of the documentary.

This wasn’t a sudden, late-life claim made for attention.

The filmmakers also brought in a forensic team to analyze imagery and footage from that day. Their conclusion was that Nick Ut could not have made the photograph from the position he described using a Leica with a 35mm lens. Even allowing for some margin of error, he was simply too far from where he would have needed to be.

The film roll characteristics aligned with a Pentax. Nghệ was using a Pentax.

Based on my own experience—nearly twenty years photographing in Vietnam, often in chaotic and emotionally intense situations—I agree with that assessment. Nick was too far out of position to have made that frame.

As for photographers or journalists who now claim they “saw” Nick take the photo, I understand the instinct to defend a friend. But in real chaos, you’re focused on your own work. During tragedy, even in far less extreme situations than this, I’ve often had no idea what the photographer next to me was capturing. In the era of film, you barely knew what you had until it was processed, let alone someone else’s frame.

Two questions come up repeatedly.

Why did Robinson wait fifty years?

Why didn’t Nghệ speak earlier?

To me, those questions aren’t complicated.

Grudges don’t generate forensic evidence. They don’t produce vantage-point analysis. They don’t conjure another photographer who was verified to be at the scene and quietly maintained the same claim for decades.

And Nghệ was a refugee. He wasn’t pursuing fame, awards, or recognition—those were largely Western constructs. For local stringers, the work was a job. A way to survive and support family.

Silence, in that context, makes sense.

What I find troubling is that many of the loudest critics haven’t spoken to the Vietnamese voices closest to the truth. They haven’t interviewed Vân, the local reporter and translator who investigated this story extensively. I’ve spoken with her privately. She understands the cultural nuances at play and strongly believes Nghệ’s account.

At a minimum, people should seek her perspective before dismissing the film.

They also haven’t spoken with Nghệ or his family. Criticism from a distance, while ignoring those most directly affected, feels hollow.

It’s also worth noting that the Associated Press reviewed the evidence and called it “inconclusive.”

They did not debunk the claims. They did not dismiss them. They said the evidence was inconclusive.

That matters. It means the door remains open.

The documentary itself isn’t perfect. I didn’t love the line suggesting that “a photographer knows what he didn’t take.” Memory in chaotic situations is unreliable, and I don’t think that framing is entirely fair. Some scenes feel staged in a cinematic way, and critiques of the narrative structure are valid.

But filmmaking style isn’t the core issue here.

The evidence and the logic are.

I don’t believe Gary Knight or the team set out to destroy Nick Ut’s legacy. That simply isn’t how Gary operates. If anything, I imagine this project involved long ethical discussions and many sleepless nights.

What I see is a team trying to address what they believe is a historical injustice and give a Vietnamese photographer recognition that was denied.

So I’ll leave you with the same question I asked myself.

Which scenario is more believable?

One: an AP editor makes an unethical decision in the chaos of war. That decision snowballs. Nick, shaped by time and memory, believes he took the photo. Robinson raises concerns quietly and is dismissed, only speaking publicly decades later.

Or two: Robinson fabricated everything. He convinced another photographer to support the claim. He fooled forensic analysts, Gary Knight, and an entire documentary team. He manufactured angles, distances, and lens characteristics—and persuaded World Press Photo to revoke an attribution for the first time in seventy years.

One of those scenarios requires far fewer assumptions.

I believe Nghệ took the photograph.

And while I feel empathy for Nick Ut, I feel even more for Nghệ—a man who lived his entire life without recognition for work that shaped history.

This may not be perfect justice. But it’s a start.