Soulless Street Photography (Updated)

There Is More to Photography Than a Human Walking Through a Shaft of Light

I’m guilty of this too. I’ve taken this photo, I’ve used it, and I’ve benefited from it. Leica, Fuji, and Ricoh are guilty of it as well, especially when you look at their monthly contests and what consistently gets rewarded. The “human walking through a shaft of light” image has become the gold standard for street and travel photography, and that’s the problem. It’s not that the image is wrong, it’s that it’s been elevated to something far bigger than it deserves to be.

Can we stop praising and rewarding this photograph as peak street or travel photography? Or at the very least, can we evolve past it and treat it as part of photography, not the entire thing?

Before going any further, let me clarify something. I’m not bitter, jealous, or angry. I’m fortunate enough to make a living as an editorial and commercial photographer, and I genuinely enjoy teaching amateur photographers through YouTube, workshops, and in-person classes. This isn’t a rant fueled by resentment. It’s about education and long-term growth.

When I say “human walking through a shaft of light,” you know exactly what I mean. It’s the image that wins countless monthly amateur street and travel photography contests, especially the mid- to low-level competitions run by camera brands.

The formula rarely changes. A large, textured wall. A dramatic shaft of light cutting down from above. A lone figure passing through that light at just the right moment. For street photography it’s black and white. For travel photography it’s color.

Composition-wise, it’s a wide shot, usually between 28mm and 50mm. It requires patience, a basic understanding of exposure, and very little conceptual thought. You expose for the highlights, you wait, and eventually someone walks through the frame. And that’s exactly why people love it.

See, I do it as well, so don’t feel bad about yourself but there is more to street and travel photography than shots like this.

See, I do it as well, so don’t feel bad about yourself but there is more to street and travel photography than shots like this.

You don’t have to get close to people. You don’t have to engage. You don’t have to take risks. You don’t have to think about story. And most importantly, contests and camera companies reward it.

The problem is that most of the time, these images lack depth, meaning, and emotional weight. Not every photograph needs to be profound, but when an entire generation is taught that this is the goal, something gets lost. I see it constantly in workshops and online—photographers doing everything “right” yet feeling empty about their work.

They’re producing clean, competent images, but they’re not saying anything. That’s because they’ve been taught visual tricks instead of visual storytelling.

Story, style, and narrative are not reserved for professionals. Anyone can find a story worth photographing. But telling that story requires intention, sequencing, and an understanding of how images work together. A single person crossing a beam of light rarely carries that weight on its own.

I’m not saying don’t photograph shafts of light but do so with purpose, to create a mood and tell a story like I did here for this story about gibbon caretaker in Malaysia.

I’m not saying don’t photograph shafts of light but do so with purpose, to create a mood and tell a story like I did here for this story about gibbon caretaker in Malaysia.

Here’s the alternative.

Commit to a project. Study photographers who spend months or years on a body of work. Pay attention to how they capture emotion, how much variety exists within their imagery, and how images are sequenced to build meaning. Start small. One simple story. Then build from there.

I promise you this: if you spend even once a week, or a few times a month, photographing a story you genuinely care about, the result will be far more fulfilling than ending up with fifteen variations of the same light-shaft photograph. A fifteen-image story will teach you more, and give you more pride, than fifteen near-identical crowd-pleasers.

Now, let’s be clear about something. This image is not the enemy.

I’ve taken it. I still take it. Many professional photographers do. It’s a tool, not a sin. I’ve used variations of this shot in photojournalism, commercial work, video projects, and even early wedding assignments. A person wearing a conical hat walking through a shaft of light has pleased clients for years.

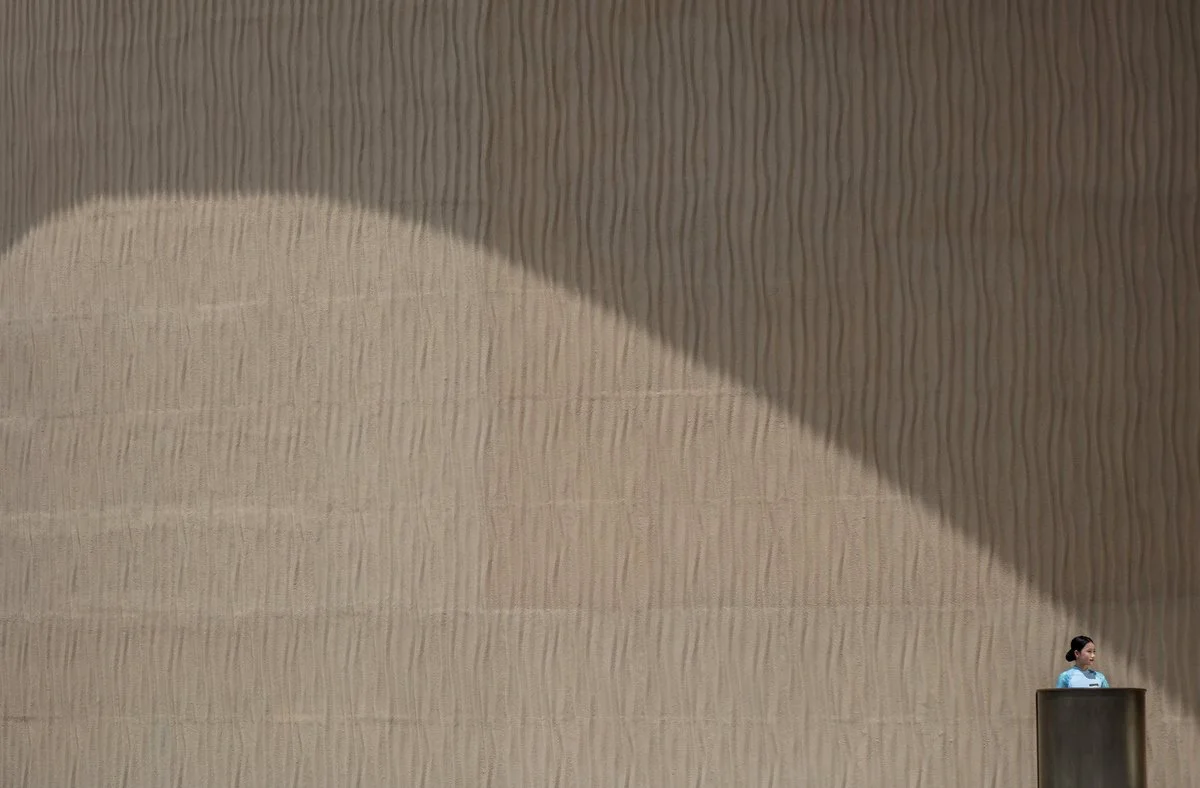

I’m using a similar technique here for our client InterContinental Hotels on a commercial shoot, but it’s not our only technique.

I’m using a similar technique here for our client InterContinental Hotels on a commercial shoot, but it’s not our only technique.

The mistake happens when it becomes the only thing you know how to do.

Some photographers build entire careers around this look, and that’s fine, not my cup of tea, but fine. But if you’re learning, growing, and trying to find your voice, relying on one visual trick will eventually stall you.

If you want to take this photo, it’s simple. You walk alleyways. You find textured walls with directional light. You expose for the highlights. You wait. Someone walks through. The amateur version is any person, any light. The elevated version is better texture, stronger geometry, dramatic light, maybe a hat. In travel photography, the wall gets colorful and the subject wears something that contrasts.

It works. That’s not the issue.

The issue is stopping there.

This image from my personal project documenting the last two northern white rhinos has more meaning to me compared to any shot of a person passing through a shaft of light. Find your version of this.

If you want depth, meaning, and longevity in your photography, you have to move beyond tricks and toward storytelling. You have to risk boredom, failure, and slow progress. But the payoff is real.

Before I go, don’t think you can hide behind the “something old in front of something new” cliché either. I’m coming for that one next. All kidding aside, the same goes for silhouettes, reflections, juxtaposition shots, keep taking them but do them with purpose and try not to become one-dimensional. More important than learning these tricks and learning when to use them to tell a meaningful story.

If this article resonates with you and you’re genuinely committed to improving, my online mentorship program and workshops are built around this exact approach.

Justin is an editorial and commercial photographer who’s been based in Vietnam for almost 20 years. In that time, he’s covered over 100 assignments for The New York Times and shot global ad campaigns for Fortune 500 companies across Asia and beyond.

Watch my full episode on this topic below.